Briefing

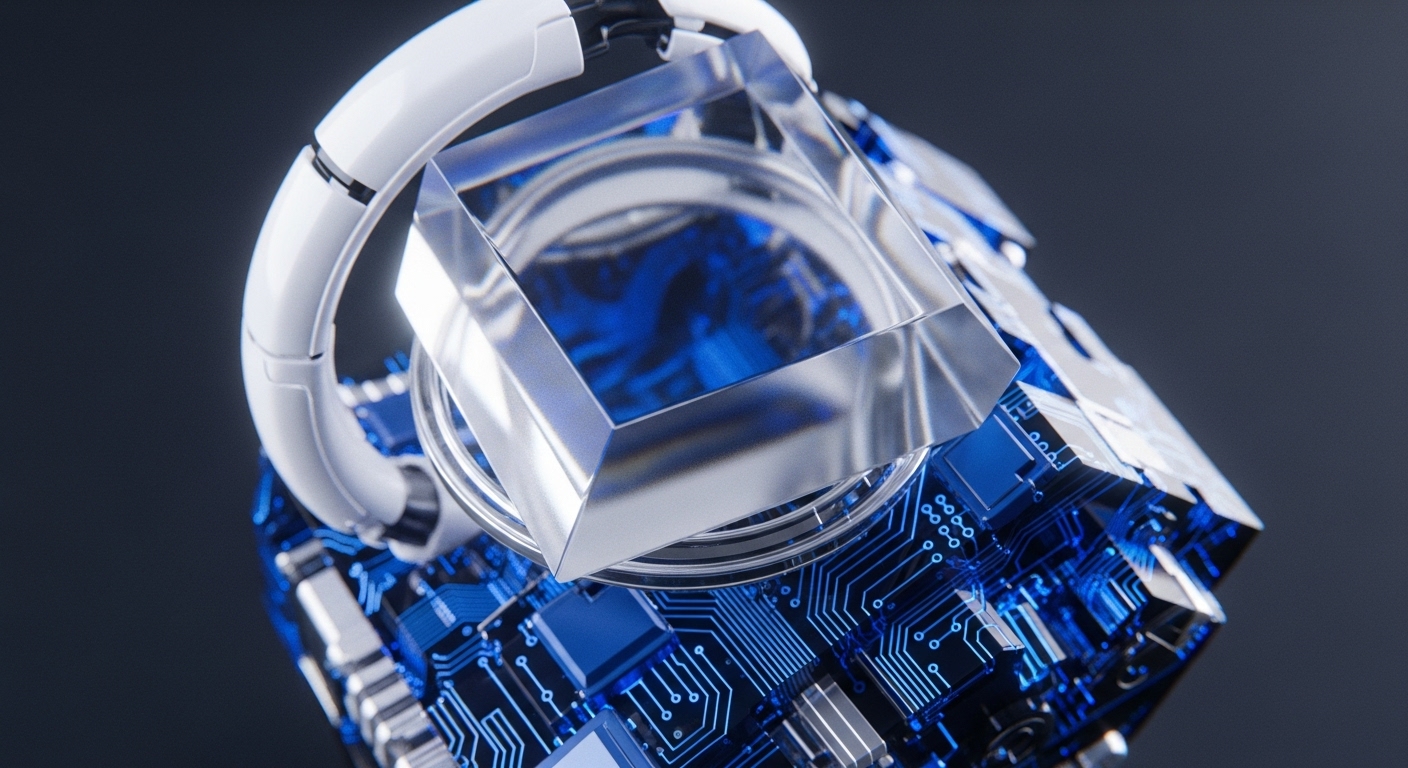

This paper addresses the fundamental problem of enforcing agreements in decentralized systems, where traditional legal frameworks are slow, costly, or non-existent, and long-term relationships are not guaranteed. It proposes a foundational breakthrough → the “digital court,” a smart contract designed to act as a self-enforcing commitment device. This digital court incentivizes agents to truthfully report violations and imposes automated fines, effectively substituting the role of legal enforcement.

A crucial aspect of this mechanism is its reliance on the subtle influence of “behavioral agents” with intrinsic preferences for honesty or dishonesty, enabling unique implementation of correct judgment even when most participants are purely rational. This new theory fundamentally redefines the scope of enforceable agreements on-chain, opening avenues for robust decentralized applications while simultaneously highlighting new regulatory challenges, such as the potential for enforcing illegal contracts privately.

Context

Before this research, the prevailing theoretical limitation in mechanism design for decentralized systems stemmed from the inherent difficulty of enforcing agreements without a trusted third party or the repeated interactions necessary for reputation-based enforcement. Traditional smart contracts, while offering automated execution, faced challenges in obtaining truthful off-chain information (the “oracle problem”), maintaining privacy for complex agreements, managing high transaction costs for extensive on-chain logic, and enforcing non-monetary actions. The core academic challenge was to design a mechanism that could credibly deter agents from reneging in one-shot interactions, without relying on external legal systems or centralized arbiters, while simultaneously ensuring truthful information input and efficient operation.

Analysis

The paper’s core idea is the “digital court,” a smart contract that functions as a decentralized, self-enforcing judicial system. This new primitive fundamentally differs from previous approaches by separating the agreement’s logic from its enforcement. The agreement itself and most communications occur off-chain, while the digital court smart contract is solely responsible for imposing fines on agents who violate the agreement. The mechanism operates by requiring agents to “self-judge” and report on the guiltiness of others.

To overcome the “oracle problem” and achieve unique, truthful reporting, the digital court leverages the existence of even a small fraction of “behavioral agents” who possess intrinsic preferences for honesty or dishonesty. Through carefully designed incentive payments, such as quadratic fines for inconsistent reports (Design 2), rational agents are incentivized to align their reports with the expected behavior of these behavioral agents, leading to a unique equilibrium where truthful judgment is achieved. Subsequent designs (Design 3 and 4) further refine this by introducing multiple reporting stages to prevent false charges and minimize the fines imposed on innocent parties.

Parameters

- Core Concept → Digital Court Smart Contract

- Key Mechanism → Self-Enforcing Mechanism Design

- Foundational Theory → Behavioral Mechanism Design

- Primary Authors → Matsushima, H. and Noda, S.

- Date of Publication → March 2020

- Implementation Requirement → Small Fraction of Behavioral Agents

- Enforcement Method → Automated Monetary Transfers (Fines)

- Key Limitation Addressed → Oracle Problem in Decentralized Enforcement

- Potential Societal Impact → Enables Illegal Collusion

Outlook

This research establishes a foundational framework for self-enforcing mechanisms on blockchains, extending the practical reach of smart contracts beyond simple automated transfers. Future research will likely explore the empirical validation of behavioral assumptions in blockchain contexts, investigate the optimal design of incentive structures for diverse agent populations, and develop advanced cryptographic techniques to enhance the privacy of digital court proceedings. In the next 3-5 years, this theory could unlock real-world applications requiring robust, one-shot contractual enforcement in areas like complex supply chain agreements, decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) governance, and peer-to-peer financial instruments. However, it also necessitates the development of novel regulatory frameworks to mitigate the potential for these privacy-preserving digital courts to facilitate illegal activities, such as bidding rings, which are currently undetectable by traditional monitoring methods.